Yoko Ono, Time Painting, 1961.

Trans/futurities:

Queering the Cyborg as a Strategy

of Transgender Disidentification

When Words Meet Images: Art History & Visual Culture Symposium

Columbia College Chicago, 2022

Arca & Frederik Heyman, still from “Nonbinary,”

video and photogrammetry animation, 2020, XL Recordings ︎

Available online at Vernon Press ︎

Available online at Vernon Press ︎Essay included in

Monsters and Monstrosity in Media: Reflections on Vulnerability

Edited by Yeojin Kim and Shane Carreon, published March 2024 by Vernon Press.

Presenting various thinkings along the lines of the body and its representations as cultural text, together with popular or recent media productions showing various bodies deemed to be monstrous as they either cross conventionally held borders or stay in liminal spaces such as between human-animal, human-machine, virtual bodies-corporeal flesh, living-death, and other permeable borders, this volume looks into the on-screen constructions of the monster and monstrosity not only as they represent notions of difference, perceived (non)belongings, and disruptions of traditional identity markers, but also as they either conceal various vulnerabilities or implicitly endorse violence towards the labeled Other.

The Abject Feminine:

Carolee Schneemann

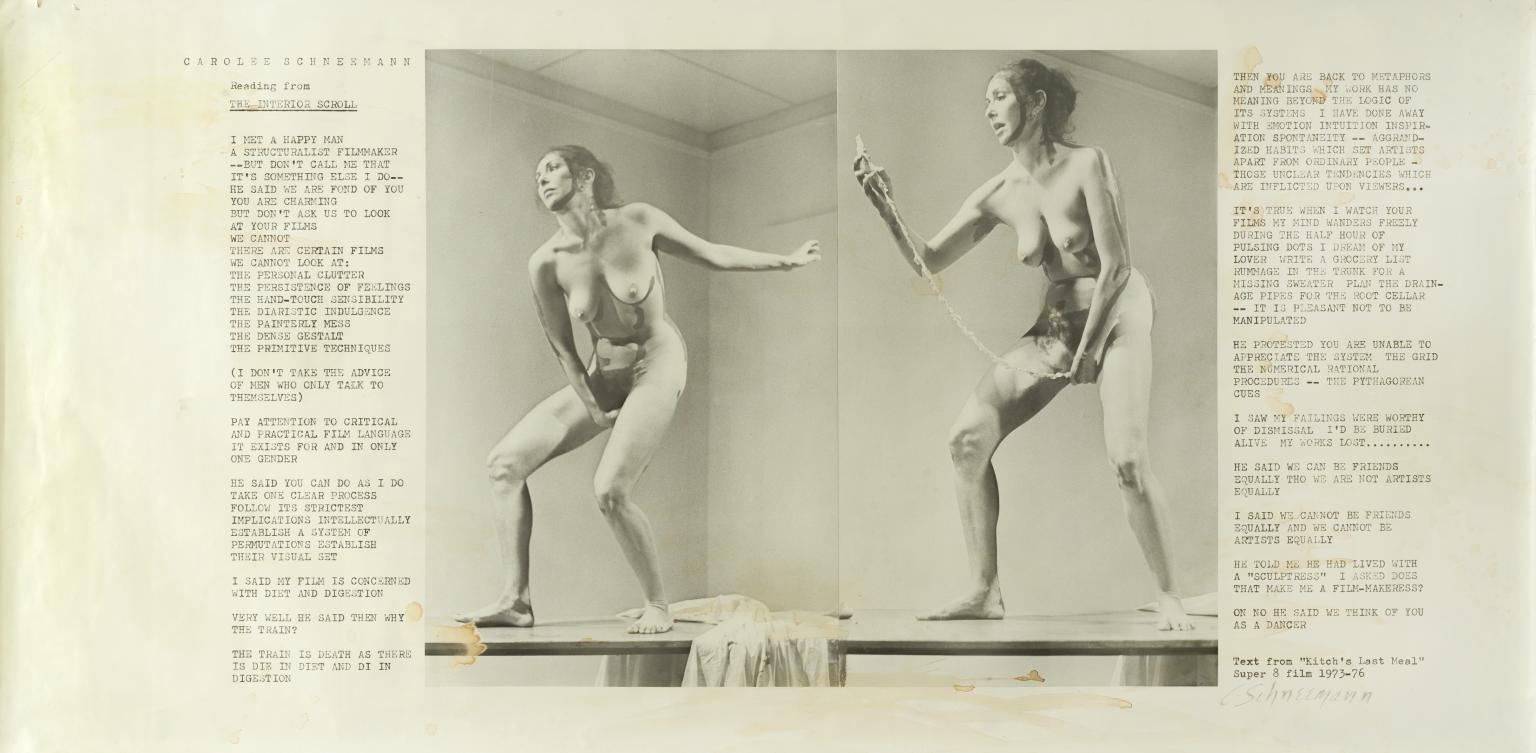

Carolee Schneemann, Documentation of Interior Scroll performance,

Beet juice, urine and coffee on screenprint on paper, 1975.

American artist Carolee Schneemann is renowned for her experimental multimedia body

of work which, spawning a career beginning in the late 1950’s until her death in 2019, explored

the body, sexuality, and gender in ways which equally shocked and engaged her viewers in

their subject and presentation. While Schneemann’s legacy is best known for her feminist

performances of the 60’s and 70’s, to disregard the artist’s own assertions that she is first and

foremost a painter, is to omit the most interesting preoccupations with the formal boundaries

of painting and drawing. In the interest of this essay, Schneemann’s work will be analyzed

according to its exploration of the abject and taboo within the social body and social spaces.

The abject is that which refers to the complex concept developed by Julia Kristeva in her book Powers of Horror, 1980. In Powers of Horror, Kristeva elaborates on the nature of the abject as functions, behaviors, and aspects of the individual or social body which are deemed to be “too impure or inappropriate for public display or discussion.” These bodily functions or attributes endanger the Judeo-Christian ideology of the divine domination of man over nature and Enlightenment theories of the evolutionary superiority of humans over animals, the aestheticized female body, and the western preoccupation with sanitation and cleanliness. Inkeeping with these concerns, artwork which deals in the abject often depicts either the bodily functions or interior in their uncensored state or their obvious remnants such as blood, bile, and ejaculate. The abject has an especially feminst context, in that the bodily functions of the female body are deemed to be particularly transgressive and corrupt the idealized female body within a patriarchal society and visual tradition. A contradictory society which prizes the product of female reproductive labor as divine yet is repelled by any visible evidence of said labor and attributes them to the impure and unclean.

“There was always physicality around us,...leaking, spilling out of boundaries, wounded farmers with bleeding limbs, hemorrhages, infections. No fantasy of the sanitized body in this household.”

In perhaps her most famous and shocking work, the artist utilized her body as a medium by which to both critique the male gaze on the female body and the white-male dominated art world which sought to criticize and minimize her artistry. In Interior Scroll (1975), Schneemann stood nude on a table, in the tradition of a posed studio model, during which she read passages from her book, Cezanne, She Was a great Painter and recounted a litany of misogynistic encounters and reactions that a female artist could anticipate in her career. She would then proceed to slowly unfurl a narrow strip of paper from her vagina, reading from the typed page as it was unwound. The scroll in question contained a screed of her own, a feminsit refusal of a contemporary filmaker and theorist’s dimissive criticism of her work as diarastic and indulgent. This performance shocked and titillated viewers, the latter of which is not readily admitted by most viwers because of the shame imposed upon taking pleasure in the abjected female body.

This is the conflicting phenomena of the abject which both attracts and repels, that which is innately near to us and at the same time is“cast off.” Even though Powers of Horror would not be published until five years later, Interior Scroll presents the abject female body in the same context as the aestheticized female figure would be for the appraisal of the male gaze whether it be the male artist or consumer alike in a feminist refusal which transgresses taboo.

The abject is that which refers to the complex concept developed by Julia Kristeva in her book Powers of Horror, 1980. In Powers of Horror, Kristeva elaborates on the nature of the abject as functions, behaviors, and aspects of the individual or social body which are deemed to be “too impure or inappropriate for public display or discussion.” These bodily functions or attributes endanger the Judeo-Christian ideology of the divine domination of man over nature and Enlightenment theories of the evolutionary superiority of humans over animals, the aestheticized female body, and the western preoccupation with sanitation and cleanliness. Inkeeping with these concerns, artwork which deals in the abject often depicts either the bodily functions or interior in their uncensored state or their obvious remnants such as blood, bile, and ejaculate. The abject has an especially feminst context, in that the bodily functions of the female body are deemed to be particularly transgressive and corrupt the idealized female body within a patriarchal society and visual tradition. A contradictory society which prizes the product of female reproductive labor as divine yet is repelled by any visible evidence of said labor and attributes them to the impure and unclean.

Carolee Schneemann’s regard for the abject began at an early age, under the influence of her father who was a country doctor in Schneeman’s hometown of Fox Chase, PA. Of her upbringing, the artist remarked that:

“There was always physicality around us,...leaking, spilling out of boundaries, wounded farmers with bleeding limbs, hemorrhages, infections. No fantasy of the sanitized body in this household.”

In perhaps her most famous and shocking work, the artist utilized her body as a medium by which to both critique the male gaze on the female body and the white-male dominated art world which sought to criticize and minimize her artistry. In Interior Scroll (1975), Schneemann stood nude on a table, in the tradition of a posed studio model, during which she read passages from her book, Cezanne, She Was a great Painter and recounted a litany of misogynistic encounters and reactions that a female artist could anticipate in her career. She would then proceed to slowly unfurl a narrow strip of paper from her vagina, reading from the typed page as it was unwound. The scroll in question contained a screed of her own, a feminsit refusal of a contemporary filmaker and theorist’s dimissive criticism of her work as diarastic and indulgent. This performance shocked and titillated viewers, the latter of which is not readily admitted by most viwers because of the shame imposed upon taking pleasure in the abjected female body.

This is the conflicting phenomena of the abject which both attracts and repels, that which is innately near to us and at the same time is“cast off.” Even though Powers of Horror would not be published until five years later, Interior Scroll presents the abject female body in the same context as the aestheticized female figure would be for the appraisal of the male gaze whether it be the male artist or consumer alike in a feminist refusal which transgresses taboo.

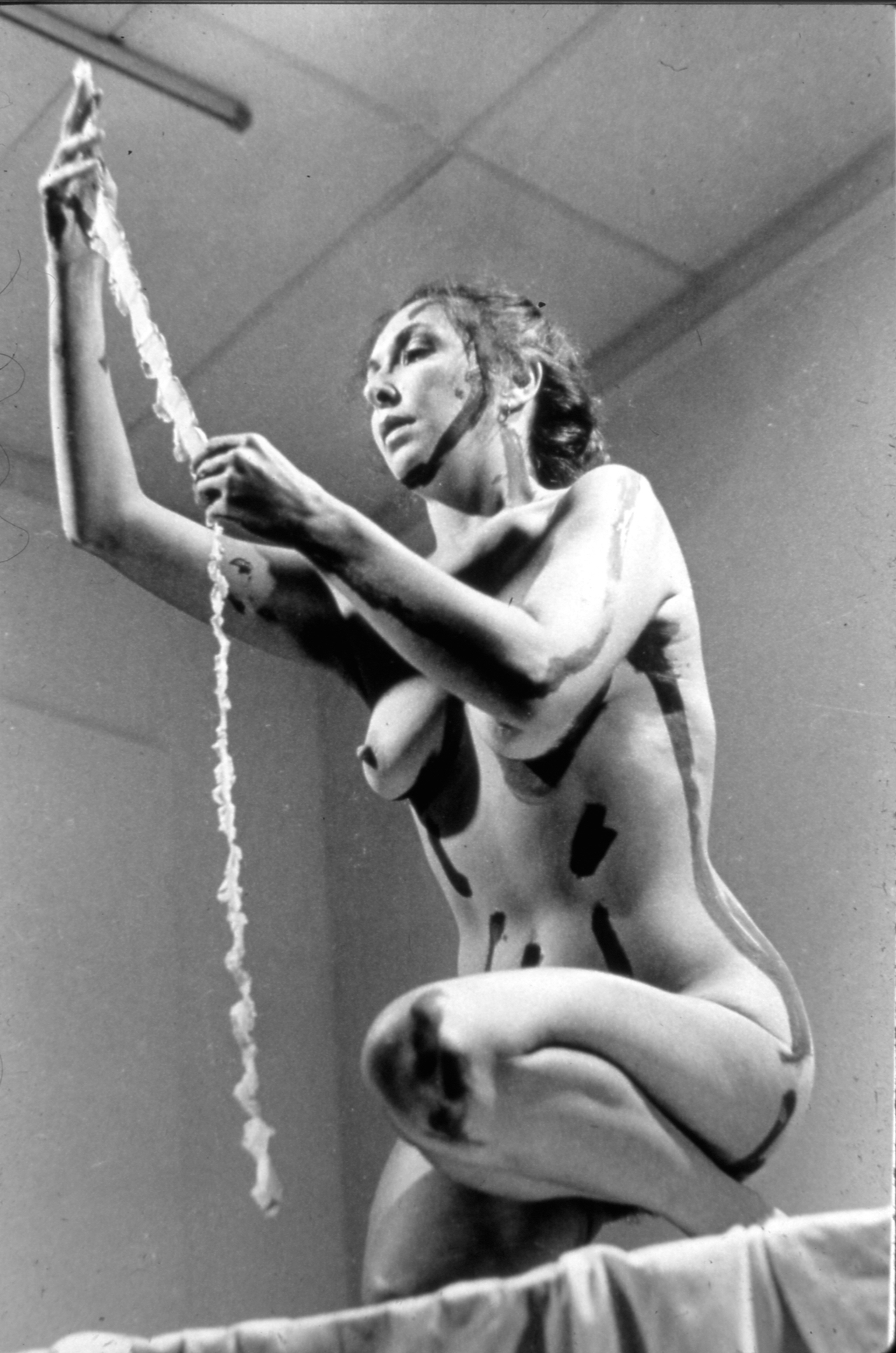

Carolee Schneemann, Eye Body #11, photo collage, 1963.

Carolee Schneemann, Interior Scroll,

1975 (Photo by Anthony McCall.)

1975 (Photo by Anthony McCall.)

As stated earlier, the full appreciation of Carolee Schneemann’s work includes her formal

experiments in mark-making, drawing upon the artist's training as a painter. Prior to the

performances and multimedia experimentations for which she is most well known, Schneemann began her career as a painter working in a gestural style alongside the abstract expressionist

movement which had emerged in the New York art scene which the artist resided. While Schneemann would reject affiliation with the abstract expression group because of its idolization

of the anguished artist and domination by male artists, Schneemann was still influenced greatly

by Pollock’s “action painting” technique and adapted its philosophy into her work. She believed that what mattered most of action painting was the

evidence of the active body in motion. Going beyond the limitations of brush onto canvas, she

instead prioritized the aesthetic of activation and began “...adding found matter to the surfaces

of her canvases, then cutting them up and adding them to three-dimensional constructions,

some with motorized components.”

Carolee Schneemann was as concerned with dissecting and rearranging how her images were constructed as she was with the way she tore down and reformed the concepts represented within them. In this way she is in keeping with Georges Didi Huberman’s argument that, “the image is best experienced as rend, that the image is a rend. The image gains its power as rend.” In addition to the material rending of medium, does Shneemann not also tear at the social fabric when she transgresses the norms of appropriate female appearance and behavior, whereby that rupture is what creates the work?

The artist’s Up to and Including Her Limits, (1973), is a work which is reflective of the transition from her early action painting influenced assemblages and her later performance based work. The performance-installation is described in the artist’s own words:

Carolee Schneemann was as concerned with dissecting and rearranging how her images were constructed as she was with the way she tore down and reformed the concepts represented within them. In this way she is in keeping with Georges Didi Huberman’s argument that, “the image is best experienced as rend, that the image is a rend. The image gains its power as rend.” In addition to the material rending of medium, does Shneemann not also tear at the social fabric when she transgresses the norms of appropriate female appearance and behavior, whereby that rupture is what creates the work?

The artist’s Up to and Including Her Limits, (1973), is a work which is reflective of the transition from her early action painting influenced assemblages and her later performance based work. The performance-installation is described in the artist’s own words:

“I am suspended in a tree surgeon’s harness on a ¾” manila rope, a rope which I can raise or lower manually to sustain an entranced period of drawing—

my extended arm holds crayons which stroke the surrounding walls, accumulating a web of colored marks,

...My entire body becomes the agency of visual traces, vestige of the body’s energy in motion.”

my extended arm holds crayons which stroke the surrounding walls, accumulating a web of colored marks,

...My entire body becomes the agency of visual traces, vestige of the body’s energy in motion.”

Schneemann performed Up to and Including Her Limits nine times between 1971 and 1976, eventually turning it into an installation consisting of “...a record of the lines her suspended body made in space as she moved it up, down, and across expansive sheets of paper placed on the walls and floor of a corner of a room. Alongside the drawing, stacked video monitors show recorded footage of her performances, while the harness and rope that held her body hangs in the center of this display.” Just as she did in Interior Scroll, the artist uses her body in Up to as the instrument, or the medium, by which she constructs the work. Schneemann’s nude body is partially bound in order to suspend her above the surface of her canvas, the appearance of which draws visual comparison to bondage and Kinbaku. While the flirtation with taboo is not the primary goal of the work, Schneemann was undeniably aware of the provocation and eroticism it could induce. Schneeman’s work has has been crticized by some second wave feminists as being counter productive to feminist ambitions, becuase they considered her explorations of sexuality and gender to be fodder for the male gaze. However, Schneemann has always maintained that her practice is a subversion and refusal of patriarchal definition. In retrospect of her trailblazing career, the artist declared that, “In 1963, to use my body as an extension of my painting-constructions...was to challenge and threaten the psychic territorial power lines by which women were admitted to the Art Stud Club.”

Aesthetics of Derangement

in Surrealist Literature

The Surrealist affinity of derangement originates in the influence of the Romantic movement of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century. The Romantics emphasized subjectivity and individualism, hailing the insane as heroic and with access to profound truths and realities. Disaffected with Western culture and seeking new forms of expression, the Romantics and the movements influenced by them sought out some primordial cognitive state which could escape the stifling regimentation of “civilized” society. The Expressionist, Primitivist, and Dadaist movements which preceded the Surrealists looked outward toward the pre-colonial cultures of Africa and Oceania, while the Surrealists looked inward to the psyche of dreams and the subconscious.

Surrealism was closely involved with contemporary developments in psychology and psychoanalysis from its inception. Heavily influenced by the theories of Sigmund Freud as well as Hans Prinzhorn, whose book, Artistry of the Mentally Ill (1922) was introduced into French surrealist circles by pioneering Dadaist and Surrealist, Max Ernst. Chafing against Western rationalism, the Surrealists regarded madness as a state of absolute freedom from logic, cultural conventions and orthodoxy, as the Surrealist poet Paul Éluard once wrote, “We who love them understand that the insane refuse to be cured. We know well that it is we who are locked up when the asylum door is shut: the prison is outside the asylum, liberty is to be found inside.” Far from pitying or ostracizing the insane from society, the Surrealists mythicized mental illness as something aspirational.

Surrealism was closely involved with contemporary developments in psychology and psychoanalysis from its inception. Heavily influenced by the theories of Sigmund Freud as well as Hans Prinzhorn, whose book, Artistry of the Mentally Ill (1922) was introduced into French surrealist circles by pioneering Dadaist and Surrealist, Max Ernst. Chafing against Western rationalism, the Surrealists regarded madness as a state of absolute freedom from logic, cultural conventions and orthodoxy, as the Surrealist poet Paul Éluard once wrote, “We who love them understand that the insane refuse to be cured. We know well that it is we who are locked up when the asylum door is shut: the prison is outside the asylum, liberty is to be found inside.” Far from pitying or ostracizing the insane from society, the Surrealists mythicized mental illness as something aspirational.

Since the art of the insane captured the interest of artists starting in the early twentieth century, many accomplished psychologists and psychiatrists have attempted to clinically define the aesthetics of derangement, to no conclusive answer. Any number of elements have been proposed, the most frequent being symbolism, anthropomorphism, formalization, deformation , de-familiarization and absurdity, however none have been unanimously accepted as innate to the art of the deranged mind. Emulating these theorized aesthetics of madness at the time, almost all of the above mentioned traits are also characteristic elements of the aesthetics of Surrealist art.

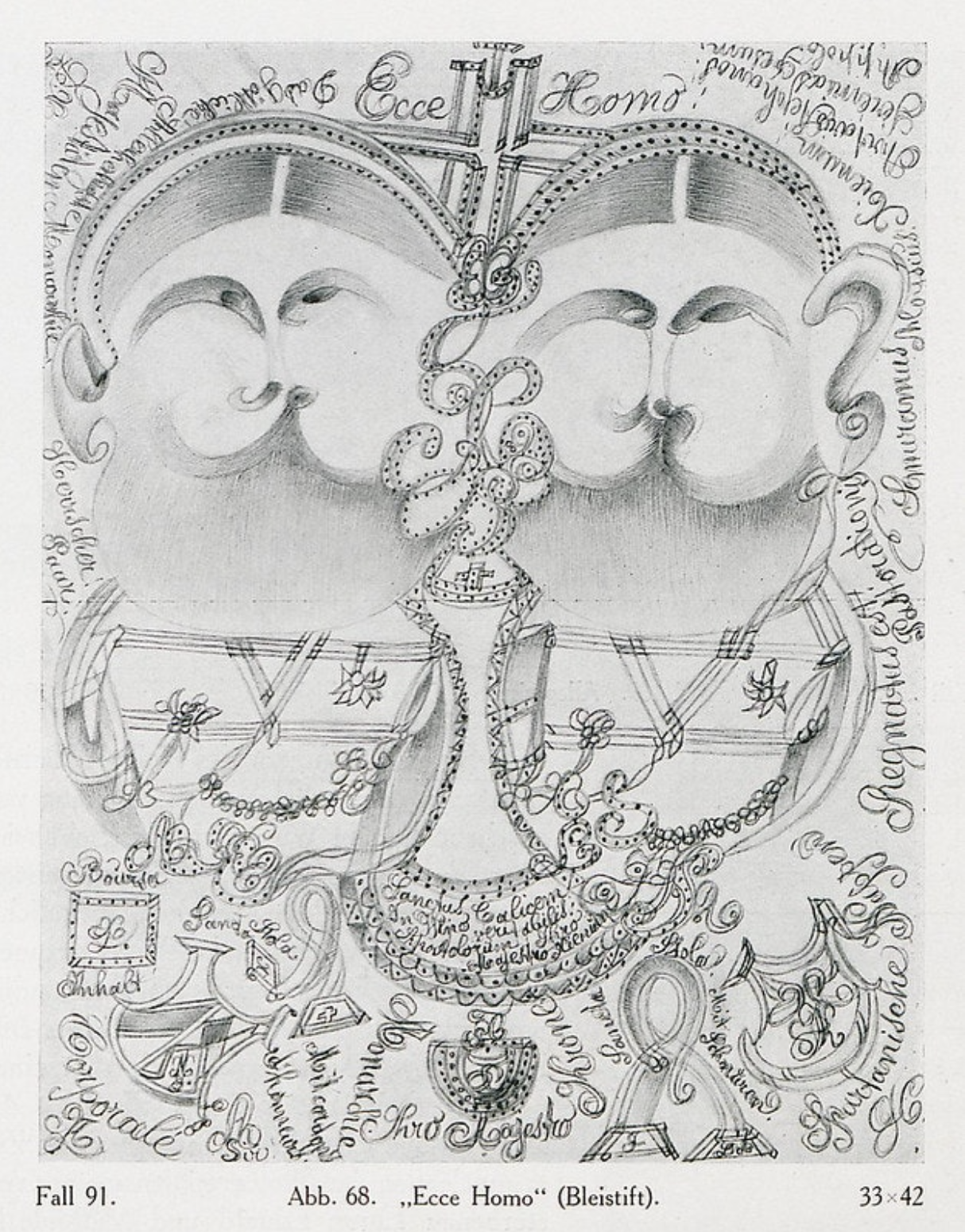

Drawings by Nadja

Drawings by Nadja featured in Breton’s Nadja.

Prior to the development of Surrealism, the movement’s founder, Andre Breton studied medicine, with a particular interest in mental illness, and was later assigned to the Pitié-Salpêtrière mental hospital during World War I. His experiences at the ward permanently altered the direction of his career and influenced the ideas which would later become the movement of Surrealism. In the first Surrealist Manifesto, Breton wrote: “The confidences of madmen: I would spend my life in provoking them. They are people of a scrupulous honesty, and whose innocence is equalled only by mine.” Breton would indeed continue to provoke the confidences of the mad, demonstrated in his second novel, Nadja (1928). In it, the author recounts his real-life affair with a strange young woman he encounters in Paris. The eponymous Nadja and Breton begin a brief but torrid relationship, which is marked by volatile emotion, enigma, and obsession. At their first encounter, Nadja is already suffering from disassociation, and spiraling into psychosis.

While at first so fascinated by her that he arranges to meet with her every single day, Breton grows disturbed and disinterested by her increasingly erratic behavior, ultimately ceasing all contact entirely. Breton is enamored with Nadja, but only so long as she continues to be his muse, embodying and affirming his own ideas of romanticized derangement. Whenever Nadja reveals any of her personal history to him, he is repulsed and becomes agitated, writing that he wishes she would tell him no more of it. Shortly after their final meeting, Nadja is admitted to an asylum. Despite recognizing that he might have contributed to Nadja’s breakdown, he never visits her in the asylum, instead criticizing the psychiatric system for institutionalizing those who do not conform to normative behavior and thinking. To recognize Nadja’s suffering caused by her unaided mental illness would be to admit the fallacy of his own theories of transcendent derangement, and wound his self-righteous ego.

While at first so fascinated by her that he arranges to meet with her every single day, Breton grows disturbed and disinterested by her increasingly erratic behavior, ultimately ceasing all contact entirely. Breton is enamored with Nadja, but only so long as she continues to be his muse, embodying and affirming his own ideas of romanticized derangement. Whenever Nadja reveals any of her personal history to him, he is repulsed and becomes agitated, writing that he wishes she would tell him no more of it. Shortly after their final meeting, Nadja is admitted to an asylum. Despite recognizing that he might have contributed to Nadja’s breakdown, he never visits her in the asylum, instead criticizing the psychiatric system for institutionalizing those who do not conform to normative behavior and thinking. To recognize Nadja’s suffering caused by her unaided mental illness would be to admit the fallacy of his own theories of transcendent derangement, and wound his self-righteous ego.

Consider, by contrast, the shorty story Down Below (1944), by Surrealist painter Lenora Carrington. After the arrest of her romantic partner, fellow surrealist Max Ernst, by the Gestapo during the Nazi invasion of France, Carrington fled to Spain where she suffered from an anxiety and delusion induced a nervous breakdown. Having been admitted to an asylum, she was treated with the drugs cardiazol, luminal, and “concussive therapy,” which induced shock and images of pain and violence. In Down Below, the artist recounts her harrowing experiences during the collapse of her personal and professional life, and subsequent mental breakdown. As opposed to Breton’s depiction of Nadja from a neurotypical perspective, molding her identity and projecting his own ideas onto her; Carrington retains control of her own story and experiences, depicting the reality of her period of psychosis with nuance, rather than romanticization.

Her painting, Green Tea (1942), was completed shortly after she had relocated to Mexico during her escape from the keeper assigned by her family to escort her to a sanatorium in South Africa. Still reeling from her ordeal, Carrington created several paintings relating to her recent experiences at the asylum. The figure of the left foreground in the garment reminiscent of cow hide is oftentimes attributed to representing the artist contained by a straight jacket. Behind her, the hedge lined park receding into the background is believed to symbolize the landscape of her native Lancashire, England. And along the lower edge, an underground cavern full of nightmarish and fantastical cadavers and creatures exists just below the pastoral scene. The painting utilizes several of the proposed aesthetics of derangement, such as symbolism, de-familiarization and absurdity to create and unsettling and dreamlike scenario.

The terrifying and dislocating experiences suffered by Carrington and countless other artists associated with Surrealism undermine its intellectual theory of an aestheticized and mythicized madness.

The terrifying and dislocating experiences suffered by Carrington and countless other artists associated with Surrealism undermine its intellectual theory of an aestheticized and mythicized madness.

Leonora Carrington, Green Tea, oil on canvas, 1942.