Aesthetics of Derangement

in Surrealist Literature

The Surrealist affinity of derangement originates in the influence of the Romantic movement of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century. The Romantics emphasized subjectivity and individualism, hailing the insane as heroic and with access to profound truths and realities. Disaffected with Western culture and seeking new forms of expression, the Romantics and the movements influenced by them sought out some primordial cognitive state which could escape the stifling regimentation of “civilized” society. The Expressionist, Primitivist, and Dadaist movements which preceded the Surrealists looked outward toward the pre-colonial cultures of Africa and Oceania, while the Surrealists looked inward to the psyche of dreams and the subconscious.

Surrealism was closely involved with contemporary developments in psychology and psychoanalysis from its inception. Heavily influenced by the theories of Sigmund Freud as well as Hans Prinzhorn, whose book, Artistry of the Mentally Ill (1922) was introduced into French surrealist circles by pioneering Dadaist and Surrealist, Max Ernst. Chafing against Western rationalism, the Surrealists regarded madness as a state of absolute freedom from logic, cultural conventions and orthodoxy, as the Surrealist poet Paul Éluard once wrote, “We who love them understand that the insane refuse to be cured. We know well that it is we who are locked up when the asylum door is shut: the prison is outside the asylum, liberty is to be found inside.” Far from pitying or ostracizing the insane from society, the Surrealists mythicized mental illness as something aspirational.

Surrealism was closely involved with contemporary developments in psychology and psychoanalysis from its inception. Heavily influenced by the theories of Sigmund Freud as well as Hans Prinzhorn, whose book, Artistry of the Mentally Ill (1922) was introduced into French surrealist circles by pioneering Dadaist and Surrealist, Max Ernst. Chafing against Western rationalism, the Surrealists regarded madness as a state of absolute freedom from logic, cultural conventions and orthodoxy, as the Surrealist poet Paul Éluard once wrote, “We who love them understand that the insane refuse to be cured. We know well that it is we who are locked up when the asylum door is shut: the prison is outside the asylum, liberty is to be found inside.” Far from pitying or ostracizing the insane from society, the Surrealists mythicized mental illness as something aspirational.

Since the art of the insane captured the interest of artists starting in the early twentieth century, many accomplished psychologists and psychiatrists have attempted to clinically define the aesthetics of derangement, to no conclusive answer. Any number of elements have been proposed, the most frequent being symbolism, anthropomorphism, formalization, deformation , de-familiarization and absurdity, however none have been unanimously accepted as innate to the art of the deranged mind. Emulating these theorized aesthetics of madness at the time, almost all of the above mentioned traits are also characteristic elements of the aesthetics of Surrealist art.

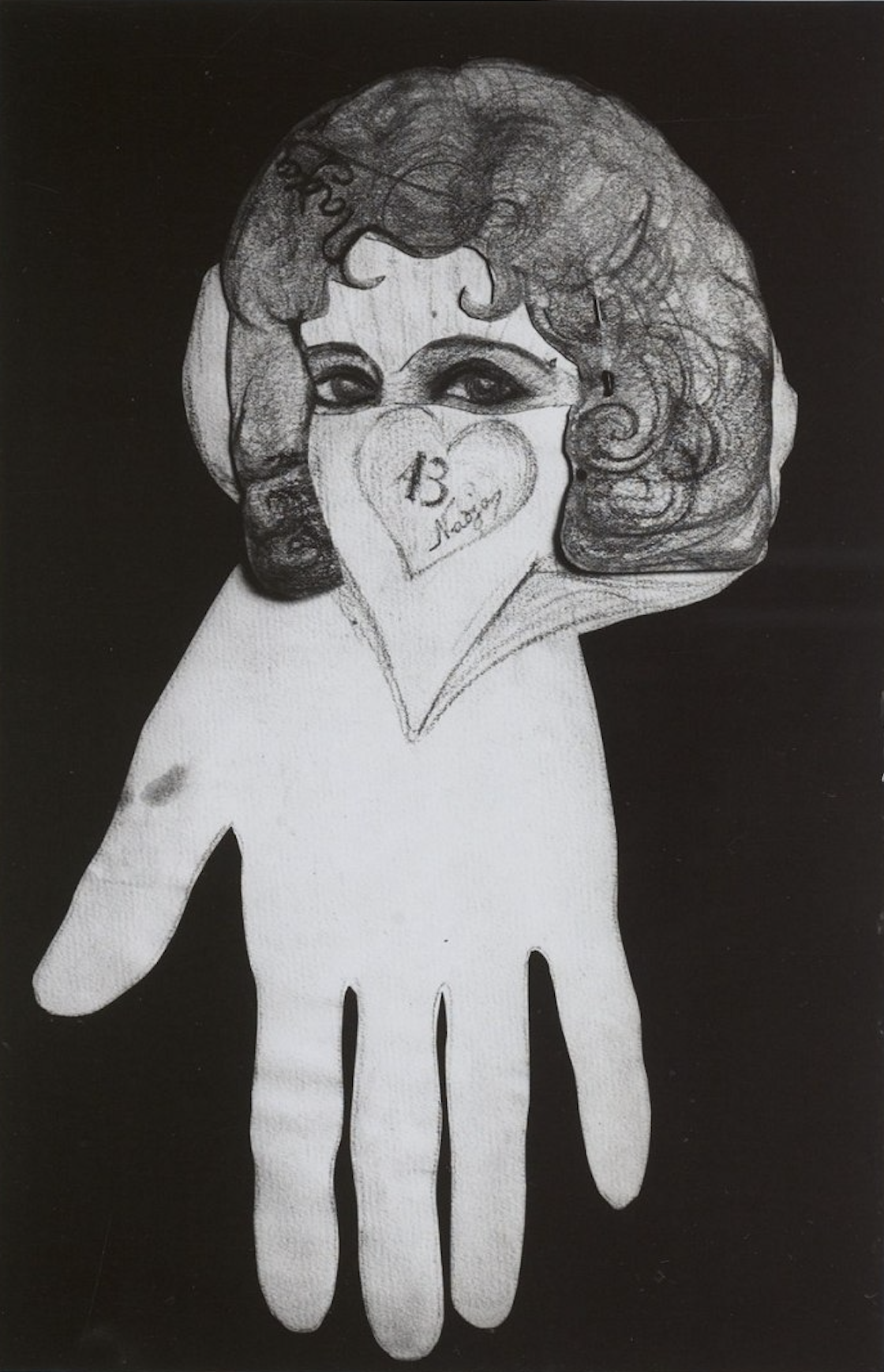

Drawings by Nadja

Drawings by Nadja featured in Breton’s Nadja.

Prior to the development of Surrealism, the movement’s founder, Andre Breton studied medicine, with a particular interest in mental illness, and was later assigned to the Pitié-Salpêtrière mental hospital during World War I. His experiences at the ward permanently altered the direction of his career and influenced the ideas which would later become the movement of Surrealism. In the first Surrealist Manifesto, Breton wrote: “The confidences of madmen: I would spend my life in provoking them. They are people of a scrupulous honesty, and whose innocence is equalled only by mine.” Breton would indeed continue to provoke the confidences of the mad, demonstrated in his second novel, Nadja (1928). In it, the author recounts his real-life affair with a strange young woman he encounters in Paris. The eponymous Nadja and Breton begin a brief but torrid relationship, which is marked by volatile emotion, enigma, and obsession. At their first encounter, Nadja is already suffering from disassociation, and spiraling into psychosis.

While at first so fascinated by her that he arranges to meet with her every single day, Breton grows disturbed and disinterested by her increasingly erratic behavior, ultimately ceasing all contact entirely. Breton is enamored with Nadja, but only so long as she continues to be his muse, embodying and affirming his own ideas of romanticized derangement. Whenever Nadja reveals any of her personal history to him, he is repulsed and becomes agitated, writing that he wishes she would tell him no more of it. Shortly after their final meeting, Nadja is admitted to an asylum. Despite recognizing that he might have contributed to Nadja’s breakdown, he never visits her in the asylum, instead criticizing the psychiatric system for institutionalizing those who do not conform to normative behavior and thinking. To recognize Nadja’s suffering caused by her unaided mental illness would be to admit the fallacy of his own theories of transcendent derangement, and wound his self-righteous ego.

While at first so fascinated by her that he arranges to meet with her every single day, Breton grows disturbed and disinterested by her increasingly erratic behavior, ultimately ceasing all contact entirely. Breton is enamored with Nadja, but only so long as she continues to be his muse, embodying and affirming his own ideas of romanticized derangement. Whenever Nadja reveals any of her personal history to him, he is repulsed and becomes agitated, writing that he wishes she would tell him no more of it. Shortly after their final meeting, Nadja is admitted to an asylum. Despite recognizing that he might have contributed to Nadja’s breakdown, he never visits her in the asylum, instead criticizing the psychiatric system for institutionalizing those who do not conform to normative behavior and thinking. To recognize Nadja’s suffering caused by her unaided mental illness would be to admit the fallacy of his own theories of transcendent derangement, and wound his self-righteous ego.

Consider, by contrast, the shorty story Down Below (1944), by Surrealist painter Lenora Carrington. After the arrest of her romantic partner, fellow surrealist Max Ernst, by the Gestapo during the Nazi invasion of France, Carrington fled to Spain where she suffered from an anxiety and delusion induced a nervous breakdown. Having been admitted to an asylum, she was treated with the drugs cardiazol, luminal, and “concussive therapy,” which induced shock and images of pain and violence. In Down Below, the artist recounts her harrowing experiences during the collapse of her personal and professional life, and subsequent mental breakdown. As opposed to Breton’s depiction of Nadja from a neurotypical perspective, molding her identity and projecting his own ideas onto her; Carrington retains control of her own story and experiences, depicting the reality of her period of psychosis with nuance, rather than romanticization.

Her painting, Green Tea (1942), was completed shortly after she had relocated to Mexico during her escape from the keeper assigned by her family to escort her to a sanatorium in South Africa. Still reeling from her ordeal, Carrington created several paintings relating to her recent experiences at the asylum. The figure of the left foreground in the garment reminiscent of cow hide is oftentimes attributed to representing the artist contained by a straight jacket. Behind her, the hedge lined park receding into the background is believed to symbolize the landscape of her native Lancashire, England. And along the lower edge, an underground cavern full of nightmarish and fantastical cadavers and creatures exists just below the pastoral scene. The painting utilizes several of the proposed aesthetics of derangement, such as symbolism, de-familiarization and absurdity to create and unsettling and dreamlike scenario.

The terrifying and dislocating experiences suffered by Carrington and countless other artists associated with Surrealism undermine its intellectual theory of an aestheticized and mythicized madness.

The terrifying and dislocating experiences suffered by Carrington and countless other artists associated with Surrealism undermine its intellectual theory of an aestheticized and mythicized madness.

Leonora Carrington, Green Tea, oil on canvas, 1942.