Tactics of Dada Photomontage

While the term photomontage was first applied in 1916 to the work of the German Dadaists, the technique is derived from earlier photographic experiments of Victorian photographers Hippolyte Bayard, Oscar Gustave Rejlander, and Henry Peach Robinson.

These photomontage precursors were referred to as “composite photographs” and constructed by trimming and arranging sections of distinct photo negatives, whose individual components would be arranged to give the illusion that they occurred in the same setting and then exposed together, creating a unified composite image.

Through their experimentations, these artists each were attempting to elevate the photographic medium to the prestige of fine art, an opinion which was not accepted by the art establishment at the time. Indeed while these early adopters of the composite photograph aspired to liberate the photographic medium from the connotations of mass production and a banal bourgeois past time, the German Dadaists embraced these qualities self-reflexively to critique the societal conditions of Weimar Germany and to disturb the sanctity of the stable image.

These photomontage precursors were referred to as “composite photographs” and constructed by trimming and arranging sections of distinct photo negatives, whose individual components would be arranged to give the illusion that they occurred in the same setting and then exposed together, creating a unified composite image.

Through their experimentations, these artists each were attempting to elevate the photographic medium to the prestige of fine art, an opinion which was not accepted by the art establishment at the time. Indeed while these early adopters of the composite photograph aspired to liberate the photographic medium from the connotations of mass production and a banal bourgeois past time, the German Dadaists embraced these qualities self-reflexively to critique the societal conditions of Weimar Germany and to disturb the sanctity of the stable image.

The technique of Dada photomontage utilizes pre-existing images and material which was circulated through mass media such as newspapers, posters, magazines, advertisements and journals. The Dadaists appropriated these images, re-contextualizing their original meaning by arranging them in defiant and transgressive combinations. The collage produced as a result is then photographed, creating a unique unified image whose smooth surface does not bear the obvious signs of alteration such as cuts, folds and seams. This quality preserves the appearance of seamless illusion.

The invention of Dada Photomontage is a contested attribution between George Grosz and John Heartfield, or Hannah Höch and her partner Raoul Hausmann, all of whom were peers among the Berlin Dada chapter. Hannah Höch is especially renowned for her use of photomontage, which weaponized the imagery of bourgeois Weimar German culture to bitingly critique its institutions of power and gender roles.

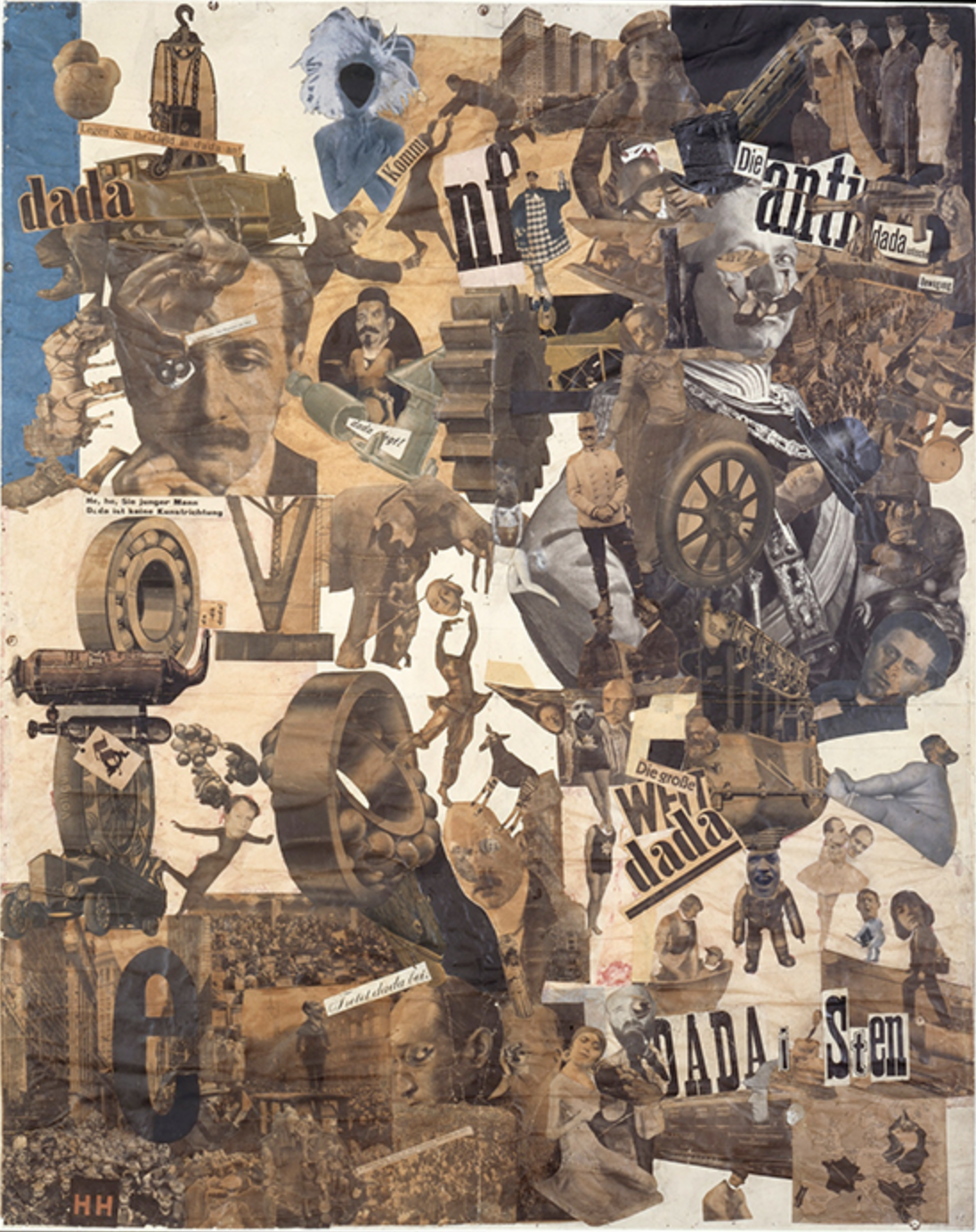

Höch’s 1919 photomontage, “Cut with the Kitchen Knife Dada through the Last Weimar Beer-Belly Cultural Epoch in Germany,” is considered to be an essential work of Dada art, and one which demonstrated the German group’s notable expression of Dada as a vehicle of political refusal.

The invention of Dada Photomontage is a contested attribution between George Grosz and John Heartfield, or Hannah Höch and her partner Raoul Hausmann, all of whom were peers among the Berlin Dada chapter. Hannah Höch is especially renowned for her use of photomontage, which weaponized the imagery of bourgeois Weimar German culture to bitingly critique its institutions of power and gender roles.

Höch’s 1919 photomontage, “Cut with the Kitchen Knife Dada through the Last Weimar Beer-Belly Cultural Epoch in Germany,” is considered to be an essential work of Dada art, and one which demonstrated the German group’s notable expression of Dada as a vehicle of political refusal.

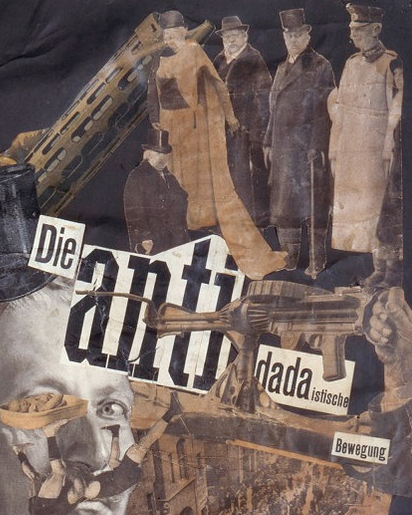

The characters and motives of the work can be divided into four approximate quadrants of the composition: the politicians, the intellectuals, the people, and the Dadas.

The upper right quadrant aligns the political leaders of Weimar Germany as being Anti-Dada, and portrays them as fascists of the bourgeois machine and urbanizing Germany. The politicians are opposed in the lower right corner by the world of Dada, featuring the faces of the German Dada artists juxtaposed in absurd and irrational combinations. Höch also includes a small suffrage map in this quadrant, which identified the countries where women had the right to vote, thus positioning Dada as supporting gender equality and possibly implying other liberal movements. Diagonally across from Dada is the establishment of intellectuals and artists, which the Dadaist adamantly disassociated themselves from. In this quadrant, Albert Einstein proclaims that,“dada is not an art trend” which imparts that the ambition of Dada was more radical than solely concerns of art. In the lower left, images of the masses incite a revolution, headed by assassinated Communist leader Karl Liebnecht who advises us to “join dada.”

In 1920’s, “The Beautiful Girl,” Höch targets a different authority of power, the patriarchal society which dictated the lives of women.

The upper right quadrant aligns the political leaders of Weimar Germany as being Anti-Dada, and portrays them as fascists of the bourgeois machine and urbanizing Germany. The politicians are opposed in the lower right corner by the world of Dada, featuring the faces of the German Dada artists juxtaposed in absurd and irrational combinations. Höch also includes a small suffrage map in this quadrant, which identified the countries where women had the right to vote, thus positioning Dada as supporting gender equality and possibly implying other liberal movements. Diagonally across from Dada is the establishment of intellectuals and artists, which the Dadaist adamantly disassociated themselves from. In this quadrant, Albert Einstein proclaims that,“dada is not an art trend” which imparts that the ambition of Dada was more radical than solely concerns of art. In the lower left, images of the masses incite a revolution, headed by assassinated Communist leader Karl Liebnecht who advises us to “join dada.”

In 1920’s, “The Beautiful Girl,” Höch targets a different authority of power, the patriarchal society which dictated the lives of women.

Höch’s status as a “New Woman,” the culturally constructed category which ascribed the emerging modern woman as young, independent, embracing androgynous fashions with a short bob hairstyle, and who eschewed home and family life in favor of joining the workforce, was a frequent subject of the artist. While urban European women were enjoying a period of increased freedom and mobility in society, those liberties were still largely permitted according to the control of men, and Höch constantly struggled against misogyny even among her male Dada cohort.

“The Beautiful Girl” critiques the male gaze and ideals of female beauty, imaging the objectification and commodification of women’s bodies through their transformation into mechanical cyborgs of a machine age, equating the fervent male desire of potent cars and machines to the sexual desire of women’s bodies.

Although commonplace today, the cut-up aesthetic of photomontage would have been a violent assault to the conventional sensibilities of the bourgeois. Herein lies the power of DaDa to upend rational images and meaning, disturbing even the stability of images. The violence of the torn image composed through photomontage was the only suitable form of visual presentation which could convey the horror and absurdity of World War I and the rise of fascism which was an immediate concern of the Dadaists of Berlin.

“The Beautiful Girl” critiques the male gaze and ideals of female beauty, imaging the objectification and commodification of women’s bodies through their transformation into mechanical cyborgs of a machine age, equating the fervent male desire of potent cars and machines to the sexual desire of women’s bodies.

Although commonplace today, the cut-up aesthetic of photomontage would have been a violent assault to the conventional sensibilities of the bourgeois. Herein lies the power of DaDa to upend rational images and meaning, disturbing even the stability of images. The violence of the torn image composed through photomontage was the only suitable form of visual presentation which could convey the horror and absurdity of World War I and the rise of fascism which was an immediate concern of the Dadaists of Berlin.